Public confidence in higher education is waning — and institutions’ leaders don’t seem terrifically cocky themselves, Inside Higher Ed’s new Survey of College and University Presidents reveals.

About a third of presidents agree that more than 10 colleges or universities will close or merge in the next year, while another 40 percent say at least five colleges will do so. And after a year in which the number of colleges either closing or merging ticked upward, nearly one in eight college chief executives predict their own institution could fold or combine in the next five years.

About a third of campus leaders agree with the statement that “the perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is accurate.”

And 51 percent agree the 2016 election “exposed that academe is disconnected from much of American society.”

Those findings aside, the survey contains plenty of evidence that campus CEOs believe strongly in their institutions’ important role and their future. To wit:

- A solid majority of presidents express confidence that their institution will be financially stable over a decade, roughly similar to results from last year’s survey.

- Presidents overwhelmingly believe the public’s skepticism is based on misunderstandings about colleges’ wealth, how much they charge (and spend) and the overall purpose of higher education.

- And campus leaders continue to say the state of race relations on their own campus is either excellent (19 percent) or good (61 percent), though two-thirds say race relations on campuses nationally is only “fair.”

These are among the findings of Inside Higher Ed’s 2018 survey, conducted by Gallup and published today in conjunction with the annual meeting of the American Council on Education, which begins in Washington this weekend. The survey of 618 campus leaders was conducted by Gallup in January and early February.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2018 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Download a free copy of the survey report here.

Inside Higher Ed’s editors will conduct a session on the survey Monday at the annual meeting of the American Council on Education. Information is available here..

On Tuesday, April 3, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the survey’s results. Register for the webcast here.

The Survey of College and University Presidents was made possible in part with support from Cengage, Jenzabar, Pearson and Wiley.

While the survey touches on a range of issues, including the price of curricular materials and presidents’ preparation for their jobs (more on those later), most of the questions and answers explore two major issues: the political and public opinion landscape for higher education, and campus finances.

Perception vs. Reality

This has been a turbulent stretch for college leaders, who have been anything but immune from the fragmentation and escalating social and political conflict in American society. The growing skepticism of institutions that candidate Donald Trump tapped into during his run to the presidency has not spared colleges and universities, as the public — in a series of surveys by Gallup, Pew and others — has expressed escalating doubts about the value of college and higher education’s contributions to the country.

To judge by the results of the Inside Higher Ed/Gallup survey of presidents, college leaders recognize that public support is slipping but believe the image hit to be generally unfair.

Only 13 percent of college and university presidents agree that “most Americans have an accurate view of the purpose of higher education,” and just 16 percent say the public has an accurate view of the purpose of their sector of higher education. The leaders of research institutions feel especially misunderstood: just 5 percent of presidents of public doctoral universities and 11 percent at private doctoral and master’s-level institutions say the public understands their sector, compared to 22 percent of community college leaders, for example.

Overwhelming majorities of presidents of all types say the public has been swayed by misconceptions about how they operate. Eighty-six percent of all presidents (and 90 percent of private college leaders) say news media and political focus on student debt has “led many prospective students and parents to think of college as less affordable than it is, taking into account student aid,” and 84 percent of all presidents (led by those at research universities) agree that attention to the minority of institutions with large endowments has “created a perception that most colleges are wealthier than they are.”

Slightly fewer campus CEOs (78 percent) say the “amenities” many colleges have used to recruit students (like the infamous lazy rivers and climbing walls) create the perception that colleges have “misplaced priorities.” And half of presidents believe attention to protests on racial issues has persuaded students and families that colleges are “less welcoming” of students from diverse backgrounds than is really the case.

Asked to assess which of several factors were most responsible for declining public support, 98 percent of presidents cited “concerns about college affordability and student debt” (65 percent said “very” responsible), 95 percent said “concerns over whether higher education prepares students for careers” (39 percent “very”), and 86 percent cited the perception of liberal political bias (31 percent “very”). Far fewer, 46 percent, said they believed an underrepresentation of low-income students in higher education was responsible for declining public confidence.

These answers varied notably by sector, though. Seventy-two percent of private nonprofit college presidents say concerns about affordability and student debt were “very responsible” for declining public confidence, compared to just under half of community college leaders.

Roughly four in 10 private college presidents put significant blame for declining public perception on large endowments, compared to o nly 22 percent of public doctoral university presidents (some of which have those large endowments). And private college presidents are twice as likely as public institution leaders (42 vs. 21 percent) to say that perception of liberal political bias is damaging public perception.

nly 22 percent of public doctoral university presidents (some of which have those large endowments). And private college presidents are twice as likely as public institution leaders (42 vs. 21 percent) to say that perception of liberal political bias is damaging public perception.

To the extent that concerns about liberal bias are harming the public’s view of colleges, the damage is likely greatest among Republican voters, as recent polls have shown that group is most likely to have lost more faith in higher education.

That divide clearly troubles presidents. More than three-quarters say they worry about Republicans’ increasing skepticism, even as 71 percent disagreed that “Republican doubts about higher education are justified.”

But the campus leaders’ answers to questions about political bias are unlikely to assuage the Republicans who cite it as a major reason for their doubts. While 62 percent strongly agree (30 percent) or agree (32 percent) that “classrooms on my campus are as welcoming to conservative students as they are to liberal students,” 16 percent disagree and 22 percent are neutral. (Only 12 percent of leaders of public doctoral institutions strongly agree.)

And while 49 percent of presidents disagree that “the perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is accurate,” a third (32 percent) agree.

Terry W. Hartle, senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, said he had just returned from the latest of several focus groups the lobbying group has done in Pennsylvania and Florida, focusing heavily on Trump voters. He said he was surprised by how little those voters seemed to care about the political climate on campuses. “They could care less about free speech,” he said. “It’s one of those issues where the political elites see it differently from the guy on the street.”

What do they care about? Price and value, Hartle says, just as the presidents are acknowledging. “They overwhelmingly think the value [of a degree] has declined, and they measure value by economic return. They think you don’t need a college education to get a good job, but their own kids are going to go to college, and they think it’s too expensive.”

Lanae Erickson Hatalsky, vice president for the social policy and politics program at Third Way, a center-left-leaning think tank that closely follows higher education issues, said the presidents probably have it right that concerns about price are the biggest driver of public dissatisfaction. She also agreed with the presidents that the “fear of student loan debt has contributed to people thinking [college] is unaffordable,” and that that misperception may discourage some students from taking out loans that might help them complete college.

Erickson Hatalsky also said, though, that the presidents seemed too inclined to attribute the declining public confidence to perception rather than reality.

“The presidents 100 percent think it’s about perception,” she said. “There’s little acknowledgment that there might be a kernel of truth” to the public concerns.

The Relationship With Washington

The 2016 election changed the landscape for many things, and higher education was clearly among them. The survey posed a series of questions about the Trump administration’s first year in office and again asked presidents some questions we asked them just as Trump was taking office. Their views of the administration (and the Republican-led Congress) have not improved.

About four in 10 presidents (41 percent) said the Trump administration’s approach to higher education in its first year has been “worse than I expected,” while half (49 percent) said it had been “about what I expected.” (Nine percent said it was better than expected.)

Sixty-two percent said Education Secretary Betsy DeVos had performed about as expected, while 30 percent said she had been worse. Leaders at private colleges were slightly more positive than those at publics, with 11 percent saying she has been better than expected, versus 3 percent for public college leaders.

On specific policies related to higher education, campus chiefs were generally critical of the approaches taken by the Trump administration and the Republican-led Congress.

The one exception was the Education Department’s efforts to “give colleges more flexibility in how they handle allegations of sexual assault,” which 54 percent of presidents said they favored (39 percent) or strongly favored (15 percent). That doesn’t mean the college leaders are fully on board with the administration’s approach to sexual assault on campus, though: more presidents said they opposed (40 percent) than favored (36 percent) the department’s decision to “revoke guidance the Obama administration gave colleges about how to handle sexual assault cases.”

Gina Maisto Smith, whose legal practice with Leslie Gomez at the law firm Cozen O’Connor focuses heavily on sexual assault cases, said the presidents’ two responses seemed in conflict — both saying “we’re in favor of more flexiblity” in adjudicating cases on their campuses but opposing the removal of federal guidance that arguably limited that flexibility. Smith said she suspected that campus leaders “understand the value of having standards of care, of having some direction,” even if they sometimes bristled at how the federal government watched over their shoulders.

Otherwise the presidents were generally opposed to policies emerging from the GOP-led government. Forty percent said they favored a plan in the House of Representatives’ bill to renew the Higher Education Act that would require minority-serving institutions that receive significant federal grants to graduate or transfer at least 25 percent of their students.

Far fewer said they backed policies that would weaken borrower-defense rules that allow some student loan borrowers to discharge their loans (27 percent), and eliminate the gainful-employment and 90-10 rules (24 percent), which have largely restricted the behavior of for-profit colleges.

And fewer still (14 percent) supported the provision in the new tax law to tax earnings on large college and university endowments.

In last year’s survey, conducted as the administration was taking office, presidents expressed concerns about Trump’s potential impact on federal support for science, the recruitment of international students and other topics. How much have presidents’ fears come to pass?

More presidents this year than last (84 percent this year to 76 percent in 2017) say Trump “does not accept scientific consensus on many issues, such as climate change,” and (by 77 percent to 69 percent in 2017) they believe that “anti-intellectual sentiment is growing in the United States.”

Where 58 percent of campus chief executives agreed last year that “international students may be less likely to enroll at American colleges” because of Candidate Trump’s anti-immigration language, 69 percent said in this year’s survey that “President Trump’s rhetoric has made it more difficult for my college to recruit international students.”

A solid majority of presidents this year (61 percent) agreed that “the push to diversify American higher education is likely to recede in public attention and public policy,” up from 55 percent in 2017.

The State of Race Relations

In one other area of potential concern — whether Trump’s sometimes incendiary rhetoric about minority groups might inflame the racial situation on campuses — the presidents are divided on the impact. Thirty-nine percent agree that race relations on their campuses are “worse under President Trump than they were under President Obama,” while 35 percent disagree.

But presidents’ other answers in the survey offer some reasons to question their credibility on this topic.

Eighty percent of campus leaders described the state of race relations on their campuses as excellent (19 percent) or good (61 percent), with private college leaders (24 percent) more likely than their public college peers (14 percent) to answer “excellent.”

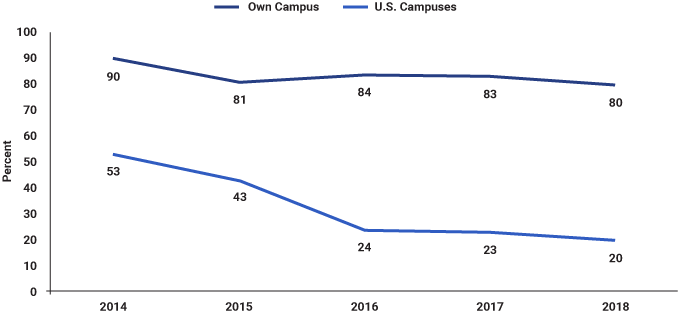

That number shows a continuing decline over the five years Inside Higher Ed has asked that question, as seen in the graph below. But as also shown in that chart, it stands in stark contrast to their assessment of the overall state of campus race relations: asked to rate race relations on campuses across the country, fewer than 1 percent say excellent and 20 percent say good.

Percentage of presidents saying race relations on campuses are “good” or “excellent”

Percentage of presidents saying race relations on campuses are “good” or “excellent”

It’s a frequent phenomenon of Inside Higher Ed’s various surveys of campus leaders for respondents to view their own campuses’ performance much more positively than everyone else’s. But it’s not clear which answer that dynamic raises more questions about — are they assuming the worst about other colleges about which they know relatively little, or grading their own campuses on a friendly curve?

Estela Mara Bensimon leans toward the latter conclusion. As director of the Center for Urban Education at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education, Bensimon works with colleges to implement the center’s Equity Scorecard, which is designed to improve the outcomes of students from underrepresented groups.

“It is hard for me to believe that race relations are excellent or good” on most campuses, she said via email. “I say this because white leaders and faculty are generally (there are always exceptions) uncomfortable with ‘race talk’ … They are more at ease with the language of diversity and inclusivity, which tends to blur the production of everyday racism through practices that are assumed to be color-blind, objective and neutral. ‘Racial relations’ play out in campus structures: curriculum, hiring, tenure, the distribution of opportunities … It is hard to see how racial relations could be deemed good or excellent when the white-Black, Latinx, Native American degree attainment gaps are higher now than they were almost 50 years ago.”

She added, “I think that presidents are so positive about the quality of race relations on their campus because it is not something they know how to assess (there is no SAT score for racial relations), it is not something they put on their cabinet meetings’ agendas, or in their reports to trustees. Most people, presidents included, view themselves as caring about being fair and not being racist so they don’t talk about racial relations. I expect that if the questions you asked of the presidents were asked of minoritized faculty, staff and students the response would be very different.”

Kimberly A. Griffin, associate professor of education at the University of Maryland at College Park and incoming editor of the Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, said she suspected presidents were drawing conclusions about other campuses’ problems based on racist acts elsewhere that may have drawn media attention. “If a campus hasn’t experienced these phenomena, perhaps the president is thinking of their campus as being in pretty good shape,” Griffin said via email.

“Unfortunately, this thinking misses the more subtle forms of oppression that students, faculty and staff face in the form of microaggressions, stereotypes, marginalization and isolation. Research tells us that these experiences are common and can be just as problematic as the incidents that may receive more media and public attention.”

Griffin said the data may explain “why we see less action and movement towards promoting race relations and engagement across difference on college and university campuses … Viewing their own campuses as ‘excellent’ or ‘good,’ while generally acknowledging race relations as a problem in higher education, signals that these presidents don’t necessarily see race relations as their problem. And you cannot begin to understand, explore or address a problem that you won’t acknowledge.”

The Financial Picture

Last year delivered a noticeable uptick in the number of colleges and universities closing or merging (or at least talking about merging), and a flurry of private colleges lowering (or “resetting”) their tuition substantially. Those developments hint at a recognition by campus leaders that the financial pressures on their institutions is a permanent condition rather than a lingering result of the Great Recession, and that structural changes may be needed.

This year’s Survey of College and University Presidents offers mixed evidence on campus chief executives’ collective state of mind about finances.

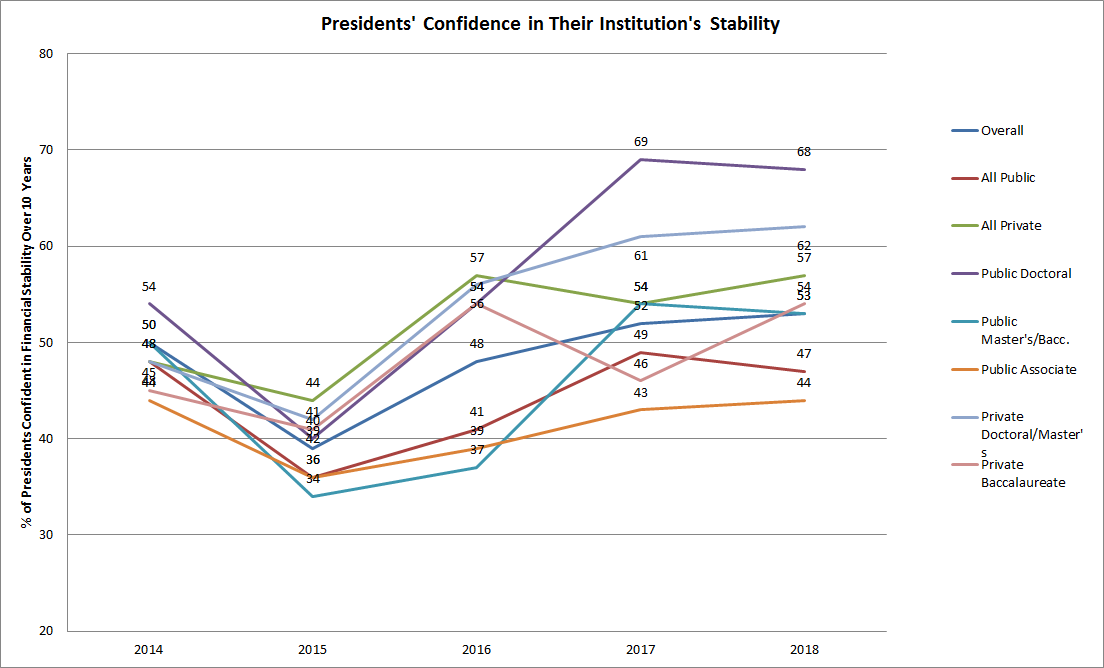

The closest thing Inside Higher Ed has to a consumer confidence index is the annual question in our presidents’ survey about their views on their institutions’ financial stability over five and 10 years. As seen in the chart below, presidents’ confidence in their institutions’ financial stability has itself stabilized, generally holding steady from last year and, for now, largely ending the kind of wild fluctuations that were evident in previous years.

Private college presidents remain somewhat more confident in their institutions’ viability over a decade, with 57 percent of leaders agreeing (21 percent strongly) that “my institution will be financially stable over the next 10 years,” compared to 47 percent of public university chief executives (16 percent strongly). The sector-specific numbers changed little from last year, with the only meaningful difference being an eight-percentage-point rise (from 46 to 54 percent) in the proportion of private baccalaureate college leaders expressing confidence in their institutions’ stability over a decade.

As has been true since Inside Higher Ed started asking presidents to assess which sectors they believed had the most sustainable business models, the presidents identified elite, wealthy private colleges and universities (79 percent and 93 percent, respectively), followed by public flagship universities (67 percent). Community colleges followed at 44 percent, with other public institutions (25 percent), private colleges (11 percent) and for-profit institutions (9 percent) lagging.

Defying Clayton Christensen and others who’ve been predicting a deluge of college closures, most presidents do not anticipate a massive increase in the number of shuttered campuses this year. (Anybody who predicted that no colleges would close or merge this year is already wrong: at least two colleges have announced closures, and at least one pair of private institutions is talking about combining operations.)

A plurality of presidents, 40 percent, expect six to 10 colleges and universities to close in 2018; 30 percent said one to five; 19 percent said 11 to 20; 10 percent said more than 20; and less than 1 percent said there would be no additional closures. Community college leaders were modestly more pessimistic on this front, with 14 percent predicting more than 20 closures, while public doctoral university chiefs were most optimistic, with 41 percent predicting one to five closures and just 2 percent expecting more than 20.

Presidents expect roughly similar numbers of public and private institutions to merge — but their estimates are modest. A majority expect one to five mergers of private and public colleges (56 and 55 percent, respectively), while 29 and 23 percent anticipate six to 10 mergers of private and public colleges, in that order. Thirteen percent of presidents expect more than 10 mergers of private institutions, and 9 percent expect that many combinations of public institutions.

Are their own institutions likely to merge in the next five years? Thirteen percent of all presidents say yes, with leaders in all sectors answering between 12 and 15 percent except those at public doctoral institutions, none of whom said yes.

Peter Stokes, a managing director at Huron Consulting Group, said the firm had spoken with numerous small private colleges and some public systems about merging or consolidating. “I think the rising cost of operations and competitive pricing environments most institutions find themselves in will continue to be challenging over the next 10 years,” Stokes said via email. “I guess the thing everyone wants to know is, who’s next — who will close, merge, partner or reinvent themselves?

“Then they want to know how institutions that have reinvented themselves have managed it. Unfortunately, it can be time consuming for institutional leaders to identify innovations undertaken by peers that could be ported to their campus, and often by the time an institution starts looking, it’s already in a difficult financial situation and yet the campus community may still not be ready to face the prospect of significant change.”

Tuition resets and freezes are less dramatic than closures and mergers, and a rash of colleges adopted them last fall, drawing praise and doubts. About two-thirds of presidents (67 percent, 17 percent strongly) agreed there would be more tuition resets at private institutions in the next year, with public college leaders much likelier than private college presidents to say so, by a margin of 81 to 60 percent.

Sixty-two percent of presidents said they expected more tuition freezes at public institutions, with larger majorities of public doctoral and four-year universities agreeing (76 and 75 percent, respectively), and with community colleges lagging at 61 percent.

Presidents do not think much of these strategies. More than two-thirds (68 percent) agreed that “tuition resets are more of a gimmick than a viable long-term strategy,” while 79 percent (and 98 percent of presidents at public doctoral universities) agreed that “tuition freezes, absent more state appropriations, can damage public institutions.”

Enrollment Questions and Doubts

Ultimately, most institutions’ financial health ebbs and flows with enrollments, and another series of survey questions explored presidents’ views on the size and composition of their student bodies. Consistent with their views on overall finances, presidents seem slightly less concerned about hitting their enrollment goals this year than in previous recent years.

Eighty-two percent of presidents described themselves as either “very” (42 percent) or “somewhat concerned” (40 percent) about meeting their institution’s “target number of undergraduates,” down from 84 percent (51 percent “very concerned”) in 2017. The numbers were down virtually across the board, in some cases sharply, as seen in the table below.

| Percent of Presidents “Very Concerned” About Meeting Undergraduate Enrollment Goal | ||

| Institution Type | 2017 | 2018 |

| Public Doctoral Universities | 23% | 10% |

| Public Master’s/Baccalaureate Institutions | 51% | 40% |

| Public Associate Colleges | 47% | 37% |

| Private Doctoral/Master’s Universities | 44% | 45% |

| Private Baccalaureate Colleges | 73% | 60% |

Asked about which particular groups of students whose enrollment they were focusing on, presidents said they were “very concerned” about enrolling students who “are likely to be retained and graduate on time” (39 percent, with 43 percent “somewhat concerned”) and students who don’t need institutional aid (27 percent). International students (17 percent) and racial and ethnic minority students (16 percent) were next.

More presidents said they were “very concerned” about giving out too much aid to students who may not need it than about recruiting first-generation students (14 percent) and Pell Grant-eligible students (13 percent). The fewest presidents said they were very concerned about enrolling classes that will improve their institution’s standing in rankings (6 percent) or talented athletes (7 percent).

Speaking Out, OER and More

The survey sought responses on a handful of other topics that didn’t fall neatly into broad topics of politics and finances.

Speaking out. Asked whether they had responded to the turbulent political environment in 2017 by speaking out more on political issues, 55 percent said yes and 45 percent said no. Private nonprofit college leaders were slightly more likely than their public sector peers to say so (58 to 51 percent).

And roughly the same proportion, 54 percent, said they intended to speak out more about issues “beyond those that directly affect” their college.

Textbooks and course materials. In line with Inside Higher Ed’s recent surveys of chief academic officers and faculty members’ views on technology, presidents strongly agreed (61 percent) that “textbooks and course materials cost too much.” Thirty percent more agreed.

Eighty-five percent of presidents also agreed (52 percent strongly) that colleges should embrace open educational resources, free and openly licensed online educational material. Doctoral university presidents, public and private alike, were somewhat less likely than their peers at other institutions to agree, at 49 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

Their support comes with conditions, though. Campus leaders were fairly divided (44 percent agree, 34 percent disagree) on whether “faculty members and institutions should be open to changing textbooks or other materials to save students money, even if the lower-cost options are of lesser quality.”

And only about half of presidents agreed (20 percent strongly) that “the need to help students save money on textbooks justifies some loss of faculty-member control over selection of materials for the courses they teach.”

Leaders of private doctoral and master’s institutions (36 percent agreed) were less amenable to a loss of faculty control than were presidents of community colleges (58 percent agree, 20 percent strongly) and four-year private colleges (24 percent strongly agreed).

Preparation for the job. Presidents were asked a series of questions about how ready they had been for various aspects of their jobs. Presented with a list of duties, campus leaders said they had been best prepared to work with faculty members (86 percent) and academic affairs (84 percent).

At least two-thirds of presidents said they were well prepared for financial management (71 percent), admissions and enrollment management (67 percent), and working with trustees (66 percent). Majorities also feel they were well prepared for public and media relations (61 percent) and race relations (54 percent). About half say the same about athletics; hot-button student-affairs issues, such as sexual assault, drinking and Greek life; and fund-raising.

The fewest identified issues of digital learning (45 percent) and government relations (47 percent).

0 Comments